Introduction

We are currently experiencing a local, and potentially global, low point in public opinion regarding crypto. Many view crypto as unsafe and unreliable. VCs, other than the ones who raised funds specifically to invest in crypto, avoid it like the plague. And among the builders, I sense a growing skepticism about crypto's potential, fearing that it might just be the world's most advanced form of gambling.

Here’s the thing: much of this is warranted. There are a lot of scams in crypto. There are even more ‘theatrics,’ such as when “DAOs” are actually operated by a small group of insiders. But if there is one comparative bright spot among this steaming pile of sillyness, it’s DeFi. DeFi, coupled with speedy blockchains like Solana, offers a compelling value proposition: a fast, cheap, globally unified financial system.

The Big Problems with the Financial System

The global financial system yields $5.5T in revenue while managing nearly $300T in assets. This existing structure is laden with inefficiencies. DeFi aims to secure a portion of this vast market by addressing two primary issues within the financial services sector:

Problem #1 - Bad UX, High Fees

You, dear reader, have probably already experienced the dreadful experience that is our legacy banking and financial systems. But in case you landed on Earth yesterday and need a little convincing, consider:

Transfers, which are basically just ledger entries and should take on the order of microseconds, generally take days to be processed.

Each bank and financial services provider generally operates as its own silo, creating high switching costs such that people usually stick to whatever they already use, even if they would be happier elsewhere.

Banks are reluctant to make even the most basic improvements to their user experiences. Consequently, a majority of banks’ apps receive less than a 4.0 ranking.

The number of consumer complaints against banks has been steadily increasing every year.

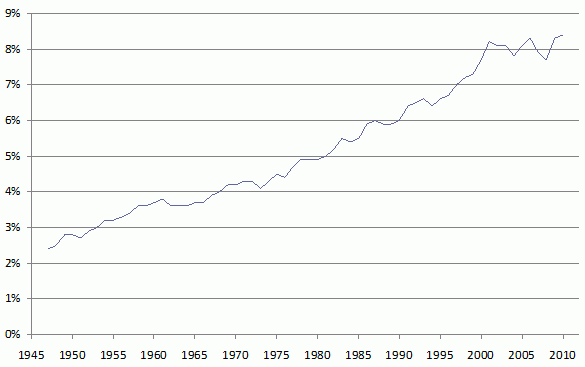

Bad ain’t cheap, either! In Europe, approximately 4% of GDP is consumed by the financial services industry. In the United States, the number is 8% of GDP, or $1.9T. To put that in context, the US spent $877B to fund its military 2022, meaning that you could pay for 2.16 extra US militaries with the resources consumed by the sector!

It wasn’t always this way. The below chart depicts the financial services industry as a percentage of US GDP - the clear trend is up and to the right.

The reason why is simple: rent-seeking. See, normally when a group of firms in an economy provide a bad service or charge too much, new entrants join the market in order to win some of their customers over. But sometimes, the incumbents are able to erect barriers to entry, such as an onerous regulatory scheme. This is what’s happened in the financial services sector. In the words of a St. Louis Fed Report, “the number of Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) insured commercial banks and savings institutions fell from 10,222 at the end of the fourth quarter of 1999 to 5,002 at the end of the fourth quarter of 2020… from 2010 through 2020, only 48 new commercial bank charters were issued.” You can also see this reflected in the financial sector’s profits, which are routinely 25% and sometimes as much as 50% of total corporate profits.

To be sure, fintech does improve this problem somewhat. Services like Plaid reduce switching costs, and neobanks like Chime and Revolut provide friendlier and cheaper interfaces to the banking system. But fintechs still inherit the structural weaknesses in the system. They can’t make your transfers go faster, send stock purchase orders to the NASDAQ on a Sunday, or solve non-abstractable ledger fragmentation.

Problem #2 - Ledger Fragmentation

I’ve drawn the below diagram as a toy representation of the global financial system. In essence:

Each jurisdiction has its own set of ledgers. For example, the US has four ledgers: Fedwire for money, Fedwire Securities for government bonds, CME for futures and derivatives, and DTCC for everything else like equities, bonds, and investment trusts.

Each jurisdiction also has its own set of firms that provide people access to those ledgers. Even when a financial services firm looks multi-national, each of those firms generally have separate operations and balance sheets.

Sitting on top of all of them do exist a few true multi-national organizations, such as international standards-settings bodies (iSSBs), the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), and SWIFT.

As you might imagine, this leads to a good deal of fragmentation. Wikipedia lists 206 central banks, each of whom - with the exception of the 20 in the Eurozone - represents a distinct financial system. Even micro-states like Vanuatu and partially-recognized ones like Transnistria have their own systems.

For example, suppose that you are a US person who wants to buy Malaysian stocks. Here’s what you would need to do:

Set up an account with a ‘licensed dealer’ (a broker, likely Malaysian-based).

Exchange US Dollars for Malaysian Ringgit and transfer them to your broker account via the correspondent banking system.

Effectuate the stock purchase.

When you want to sell, do the reverse.

Malaysia has no capital gains tax. But if it introduces one, you’ll need to pay it.

Basically, unless you use one of the two hacks described below, you will need to create accounts in a country’s financial system before you interact with people or firms in that system. Although you may not like this, the incumbents love it. A market structure where firms only compete within the same country, and not globally, is a market structure that allows high profits and rent-seeking.

Hack #1 - Platform Americana

But we live in a globalised world. It’s obviously not practical for merchants who sell overseas to create bank accounts in all the jurisdictions that their buyers might be, or for people who want to buy overseas stocks to create bank and brokerage accounts in all the jurisdictions that they want to buy in. So we’ve invented a few hacks. I call the first hack platform Americana.

The platform Americana hack is exactly what it sounds like: using the US financial system as a common hub. Some examples of platform Americana at work include:

We do the vast majority of our international trade in US dollars.

Many companies outside the US list exclusively on US exchanges, such as Spotify (NYSE: SPOT), Coupang (NYSE: CPNG), and Atlassian (NASDAQ: TEAM).

Many more, such as Alibaba, SAP, and AstraZeneca either cross-list their shares on US exchanges or have American depository receipts (ADRs), trading in the US markets.

So if you’re a Saudi oil tycoon who wants to buy some Nintendo shares, the success of platform Americana means that your trade will probably never touch Tokyo. Instead, you will likely use US dollars to buy Nintendo ADRs through an NYC-based broker.

Hack #2 - Bridging

The other strategy for getting around this fragmentation is bridging, which is when one service connects multiple underlying platforms.

A successful instance of this can be seen in the credit card networks. When you have a Visa card, you can spend it anywhere that accepts Visa cards, whether they be in Germany, Indonesia, or Djibouti. On the back-end, Visa helps your bank (the ‘issuing bank’) and the merchant’s bank (the ‘acquiring bank’) settle via the correspondent banking system. Merchants may not like the 2-3% fees, but the vast majority of this fee is composed of interchange, which the issuing banks can and do pass on to the consumer in the form of rewards. Visa and Mastercard themselves only capture 10-20 basis points of the transaction, which is non-zero but also probably not large enough to motivate a shift to a new system.

Outside of retail payments, bridging is much less pervasive. Fintechs like Wise, Revolut, and Fi are currently attempting the ‘one account to rule them all’ approach, which entails the fintech providing a single UI and then connecting to multiple banks and brokerages in the back-end. But for the most part, financial accounts are still tied heavily to a single jurisdiction and set of ledgers. Visa and Mastercards’ successes were the product of many accidents of history, including there not being incumbent payment networks in most countries at the time that Visa and Mastercard were internationalising. On the other hand, the fintechs are entering markets with clear incumbents who generally have a strong political muscle. Many of these ‘one account to rule them all’ firms have already encountered regulatory headwinds, and I suspect that this will continue.

DeFi: The Fast, Cheap, Globally Unified Financial System

The Vision

So, what do we do? Must we simply accept that TradFi is here to stay, whether we like it or not? Or do we double down, becoming more radical in our approach?

DeFi represents the second option. I think the central ideas behind DeFi can be best explained through a dialogue. So suppose that JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon has a younger brother, Johann Dimon, and that Johann personifies DeFi. Here’s a conversation that could reasonably transpire between Jamie and Johann:

Johann: You impose an 8.5% tax on the economy. I’m going to bring that down to something much more reasonable, like 0.5%.

Jamie: Oh yeah? And how are you gonna do that, kid?

Johann: I will simply create a single ledger, or a small number of interoperable ledgers, to store all of the world’s assets. This ledger will be Turing-complete, so that things like order books and ETFs can exist natively on the ledger.

Jamie: Turing-complete? What is that, a magical spell? Anyways, it’s never gonna work. Who’s going to trust you? And even if they did, my buddies in Washington would shut that down in a heartbeat.

Johann: You pose two problems, and I respond with one solution: decentralization. The ledger will be decentralized such that I won’t be able to manipulate it and the regulators won’t be able to shut it down. Programs, which I’ve started calling smart contracts, will be managed by decentralized organizations.

Jamie: How are you gonna have rules? You need rules, kid. Otherwise, the man on the street is gonna lose his shirt.

Johann: Our system will have plenty of rules. They will simply be enforced by code and game theory, not by the barrel of a gun. Unlike yours, they will be completely fair. Our justice system will show no preference for those who wheedle their way into ’the right circles.’

Jamie: I don’t know… it sounds risky…

These are the core ideas behind DeFi. Concretely, we build credibly-neutral, highly-available, and turing-complete ledgers (public blockchains), and deploy onto them regulations enforced by code (smart contract protocols) and by game theory (DAOs). This is depicted in the below diagram.

This scheme has a number of advantages over the existing system, including:

Fast: high-performance chains have settlement times close to a second. Given that most legacy financial transactions settle on the order of days, this is an improvement on the order of 10,000x - 100,000x.

Cheap: both because the costs associated with DeFi are smaller and because the market isn’t encumbered by regulatory capture, DeFi will naturally gravitate towards providing cheaper prices than the legacy financial institution. Case in point: while some banks charge upwards of 8% to exchange currencies, this can already be done in DeFi (via stablecoins) for near-zero cost.

Automated: the internet has been in mainstream use since the early 2000s, and yet many financial services firms require you to do things like call them or mail them forms. Too many New Jersey residents work in the proverbial ‘back office,’ doing work that a machine could do. DeFi represents a paradigm shift from human-centric finance to code-centric finance, decreasing the likelihood that humans are unnecessarily interposed between consumers and the financial system.

Drastically reduced counter-party risk: since you are interacting with open-source software, with generally limited human interaction, there is much less counter-party risk than the existing system. Most consumers probably don’t think about counter-party risk except for in times of turmoil, but they pay for it in the form of the firms’ compliance budgets (which are often substantial).

Atomic: for some types of financial transactions including arbitrage, it helps a lot for transactions to be atomic such that either all parts of the transaction go through or no parts do. Public blockchains provide this. It is even possible for DeFi participants to procure flash loans, wherein anyone can obtain an infinite amount of money without pre-approval as long as they pay it back within the same transaction.

Inclusive: 850 million people globally don’t have government identification. This largely prevents them from accessing the KYC-gated financial system. DeFi need not be KYC-gated, and many of its contributors (including myself) even work pseudonymously.

Open: while the causes of the 2008 financial crisis are still debated, it’s indisputable that one of them was a lack of transparency. Only an insider would have been able to see all of the rehypothecation that was occuring. In contrast, DeFi is so open that bad behavior can often be detected by people who have no other tool than a block explorer, such as zachxbt.

Globally unified: most importantly, because blockchains are credibly-neutral and decentralized, it’s possible to put all the world’s assets on a single ledger without trusting a single nation. For example, that someone cannot force the Iranians out of the system simply because one person or polity has decided that they should be ejected. The blockchain is as much China's as it is America's. So eventually, once DeFi’s kinks are worked out, regulators outside the US may prefer DeFi to the current platform Americana status quo.

All of that is not to say that there aren’t any drawbacks to the new system. For example, maybe we don’t want rogue states like North Korea to be able to use the same system as the rest of us?

But even if it’s not a Pareto improvement, DeFi represents a 10x technological improvement over the existing system. And 10x improvements tend to win in the long run, whether we want them to or not.

How we get to Mainstream Adoption: Primitives, then Assets, then Customers

As is often the case with N-sided marketplaces, DeFi’s adoption won’t happen overnight. Instead, I expect DeFi’s arc to go through three stages: primitive-building, asset-onboarding, and customer acquisition.

Primitive-Building

This is the stage we’re currently in. It entails programmers creating the fundamental building blocks of DeFi, such as order books, lending pools, tranching and fixed income protocols, asset management protocols, privacy protocols, insurance protocols, futures and options protocols, DAO protocols, and protocol aggregators. All the protocols!

Because this stage is before many assets have been onboarded, it’s the stage that looks the most self-referential and ponzi-esque.

Asset-Onboarding

The second stage is where all of the assets get onboarded. Assets can be onboarded in three ways:

ADR-style, where you have a central issuer who maintains custody of the asset and who issues a tokenized version of that asset on-chain. This is how centralized stablecoins like Circle’s USDC work, for example.

Via synthetics, where makers sell exposure to a certain financial asset.

Today, we’re already somewhat in the asset onboarding stage when it comes to currencies. We have had USD-based stablecoins for a while, and we're starting to see stablecoins for other currencies such as Euros, Yen, Pounds, Yuan, Australian Dollars, and Canadian Dollars. FX is already cheaper in DeFi, and this experience will only get better over time.

We lag a bit behind when it comes to financial assets. Since regulation is more of a hurdle here, I expect CDP-style and synthetic assets to lead the charge, and then ADR-style issuance to follow. We may even see the day when companies cross-list their shares in DeFi!

Customer Acquisition

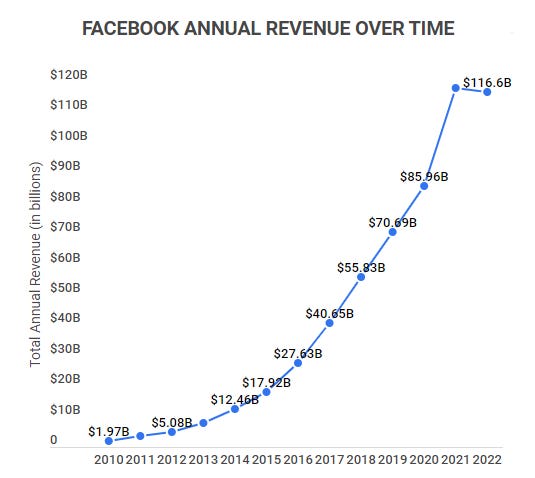

As a product gets better, its ability to attract new customers and retain existing customers increases. As such, the bulk of customer acquisition will happen after all the primitives have been built and most of the assets have been onboarded. This is not too different from web2. For example, Facebook grew its revenue more from 2018-2021 than during the entire 14 years of its prior existence.

Today, most users are speculators. That’s okay: the speculators help get DeFi’s flywheel spinning. We will start to see normal users adopting DeFi once interfaces are better and once more assets are onboarded.

Putting it all in Perspective

Putting it all together, I think DeFi’s adoption curve will look something like the below. There will be users, assets, and protocols during all three stages, but most useful protocols will be created during the current period, most useful assets will be onboarded during the second period (probably starting within 1-2 years), and user acquisition will be a long S-curve where the global population gets onboarded onto this new system.

probably one of the best pieces on DeFi I ever came across